Not exactly traditional jazz; but this is a story of interest to every musician.

|

| Theodore Brailey |

Theodore was known to his friends as ‘Ted’, so I shall call him that.

Ted was born on 25 October 1887 to parents who lived in Clarendon Road, Walthamstow, London.

His birth certificate gave his first names as William Theodore, but he seems later also to have acquired the name Ronald, possibly at baptism, or as a nickname. As a boy, he must have had piano lessons, for he became an accomplished pianist. In October 1902, not yet fifteen years old, he joined the Royal Lancashire Fusiliers. A year later, he was appointed as a regimental bandsman. (I am indebted for the facts above to my correspondent Steve Trusler who has been researching the family history for several years. Steve's grandmother was a cousin of Theodore Brailey. Steve would be happy to communicate with anyone who has information or an interest in the subject. Contact Steve at stevetrusler54[@]hotmail[dot]com .)

According to recent books, Ted learned also to play the flute, the violin and the cello while in the army. We are also told his military experiences took him to South Africa and the West Indies. I am inclined to believe these facts are true.

Ted is believed to have left the army early after five years' service.

By the age of about 20 he was working as a professional pianist in

He specialised in what we would call ‘easy listening’ - popular light music of the day. Ted played in the little orchestra of the Southport Pavilion, right next to the sea. Its 'bandmaster' is said to have been Edgar Heap - a man not much older than Ted himself.

|

| This is where Ted played piano in the Orchestra. |

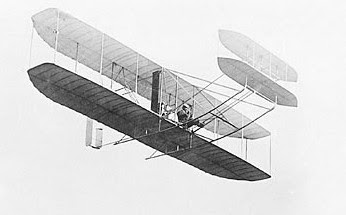

Ted had another passion: aviation. This was the time when pioneer aviators were exciting the public. Wilbur and Orville Wright had flown the world's first manned, heavier-than-air, powered aircraft in 1903, when Ted was 15.

About 4 miles from Southport (on the road to Liverpool ) was Freshfield, where a young local businessman, Mr. Cecil Compton Paterson, was setting up one of England

|

| Paterson's Airstrip at Freshfield. |

He spent eight months and £625 building his first aeroplane, whose top speed was 41 miles an hour. Soon Paterson

Occasionally he would allow a guest to fly with him. This would involve fifteen minutes or so of flight over the sea at Southport . Several other aviators started to join him at Freshfield, each bringing an additional plane. One of them was Gerald Higginbotham, who had to swim ashore after his biplane crashed in the sea.

Our pianist Ted, excited by the prospect of flying, became a friend of Paterson

I think the two young men met in the bar at The Grapes Hotel, Freshfield, where the gregarious Paterson

Ted enjoyed some flights with him, and may even have been allowed to try the controls. Such flights would have been no longer than six miles or so, at very low heights.

One of the recent books ('Titanic' by Anton Gill) says The Southport Visitor reported that Ted even designed a plane of his own and got it to fly several hundred yards. (Gill's book, by the way, also claims that Ted wrote an operetta, called The Fairies' Tribute to the Coronation).

One of the recent books ('Titanic' by Anton Gill) says The Southport Visitor reported that Ted even designed a plane of his own and got it to fly several hundred yards. (Gill's book, by the way, also claims that Ted wrote an operetta, called The Fairies' Tribute to the Coronation).

Ted also found himself a lovely girl-friend in Southport , Miss Teresa ('Terry') Steinhilber of St. Luke's Road. Her father was a German watchmaker: hence her unusual surname. She was two years younger than Ted and she worked as a milliner. Her home was just a mile from the Pavilion where he was employed. Probably they met when she attended one of the concerts. They became engaged.

(Incidentally, in 1923 Teresa Steinhilber changed her name by deed poll to Teresa Terry. My guess is that this was because of the unpopularity of German-sounding names after the First World War.)

(Incidentally, in 1923 Teresa Steinhilber changed her name by deed poll to Teresa Terry. My guess is that this was because of the unpopularity of German-sounding names after the First World War.)

So picture Ted, a very talented musician of about twenty-two, planning to marry and working in Southport , just eighteen miles north of the docks of Liverpool. It is not surprising that he was tempted to take a step up in his musical career by applying for a job on the liners crossing the Atlantic to New York

He got himself on the books of the music agents – C.W. Black and R.N. Black of Castle Street Liverpool . This was the company that supplied musicians to play on the liners sailing from Liverpool and Southampton. Possibly Ted’s impressive publicity photograph helped: as you can see (photo above) he looked smart and dapper in his top hat and wearing a carnation.

Ted must have been thrilled when Blacks booked him to play on the great Cunard steamer Carpathia which, conveniently, sailed from Liverpool .

And he made some crossings of the Atlantic on that ship. He became friendly on the Carpathia with a fellow musician, the French cellist Roger Marie Bricoux, who was six years older than himself. Roger, who came from Lille Monaco

Naturally, Ted and Roger heard about the sensational new ship the Titanic, the largest and most luxurious passenger steamship in the world, built in Belfast and soon to make its maiden voyage to America (from Southampton, rather than Liverpool).

What a thrill and honour it would be to provide the music on that great historic journey. They both applied.

They must have been highly-regarded in their profession because they were indeed chosen by Blacks to be two of the eight players on the Titanic.

So they completed their final crossing for the Cunard Line with the Carpathia in New York 2 April 1912 and got back fast to England Southampton on April 10.

|

| The Titanic during the boarding of passengers |

Maybe he intended one day to settle as a musician in London (like his colleague on the Titanic Georges Krins) and bring his wife there.

The eight musicians were not ship’s employees on the Titanic in the way the crew were. All eight were officially employed by, and under contract to, Blacks, so (and this may surprise you) they had to travel on the Titanic with tickets, as passengers. This unfortunately affected their status for insurance purposes and was to cause considerable hardship for their families. But they were certainly not in first-class accommodation. Diagrams show their quarters were very cramped.

The musicians (six string players and two pianists) were under the leadership of 33-year-old Wallace H. Hartley (violinist) of Dewsbury.

He had led orchestras at the English holiday resorts of Harrogate and Bridlington and had worked on the Mauretania for the Cunard Line. The Mauretania itself had been a sensational new ship at the time of its maiden voyage as recently as 1907.

The players probably knew each other slightly through previous musical activities, especially on the ships. But despite what people today believe, they were not an eight-piece band. What happened was that they formed two groups (a piano quintet and a piano trio) and these performed simultaneously in various locations. They all played from printed music. Dozens of arrangements were carried. The pianists had to be specially good: with the limited number of players they would sometimes have to cover the parts of various orchestral instruments.

There were seven pianos (five of them grand pianos) disposed throughout the ship. So the trio (in which Ted and the two Frenchmen Roger and Georges played) and the quintet could set up and perform wherever there was a piano.

Concealed by palms, they would play discreet background music during dinners, or light entertainment in smoking or card-playing areas. Easy-listening salon music was what they offered each evening as background for diners in first class. It would have included light music, selections from operas, polkas, ragtime and so on – Offenbach and Strauss, for example. Oddly enough, there was no dancing, so they were not required to play for that.

But, as everybody knows, their employment lasted little more than four days.

Probably among their final duties some of the musicians played to accompany hymns for the Sunday service, led by the ship’s captain.

A few hours later, on the Sunday evening, the Titanic struck the iceberg.

There have been plenty of myths about The Band of the Titanic. I remember long ago being told they were a Salvation Army band. That is obviously nonsense.

I have been told they played ‘Nearer My God to Thee’ as the ship sank. But this account has been convincingly challenged and there is virtually no hard evidence for it. I believe it was a good story cooked up by an enterprising newspaper man of the time.

It is just possible the band’s final tune was a hymn: Mr. Hartley came from a Methodist background. But there is credible witness evidence that their final number was Archibald Joyce's Songe d’Automne and I think this is most likely.

The facts about what they did during the period of two and a half hours while the ship was sinking are (as I see them) these. Mr. Hartley (regarded ever after as ‘the bandmaster’) called both groups together to play while passengers started to notice that something was wrong. The eight musicians (regarded ever after as 'The Band of the Titanic') played an hour or more of cheerful, calming music, some of it ragtime. They had to use one of the two upright pianos because that was the only one available at the spot where the passengers were gathering.

I think Mr. Hartley had not appreciated the seriousness of the situation. He pictured himself as simply entertaining people while they were unduly nervous. (Some have suggested it was a pity he gave the false impression that there was nothing to worry about. This could have contributed to the huge loss of life.)

Eventually it became clear the matter was very serious indeed. And here’s where the respect for those musicians really comes from: rather than seek safety, all eight of them chose to GO ON PLAYING, right up to the moment when they were – I presume – tipped over and into the sea. All of them drowned.

Several of the survivors later praised the courage shown by the musicians.

It may seem a strange thing to say but – having known many musicians and their curious senses of humour and of fatalism – I do not find it hard to imagine them making a few cynical remarks to each other and then deciding they might as well ‘go for it’ and give the playing their best shot.

Ironically, it was the Carpathia, on which Ted and Roger had worked earlier in the month, that picked up the first survivors of the Titanic!

When the newspapers heard about the musicians, they made the most of it. The ‘band’ became international heroes for facing death with immense dignity.

Mr. Hartley’s body was found. He was buried in his native town of Colne Lancashire , England.

Incidentally, in March 2013, it was claimed that Mr. Hartley's violin had been retrieved - as well as his body - and that the instrument had turned up in an attic! It was to be auctioned. But some scholars - while accepting that this particular instrument had belonged to Hartley - did not believe it was one he took with him on the Titanic.

Incidentally, in March 2013, it was claimed that Mr. Hartley's violin had been retrieved - as well as his body - and that the instrument had turned up in an attic! It was to be auctioned. But some scholars - while accepting that this particular instrument had belonged to Hartley - did not believe it was one he took with him on the Titanic.

The Titanic had 2223 people on board. 1517 of them perished.

The five other musicians, by the way, were these. John (Jock) Law Hume was a violinist from Dumfries , Scotland South London . John Frederick Preston Clark (‘Fred’), aged 30, played string bass and viola; he had been in variety theatre orchestras and lived in Tunstall Street, close to Liverpool Docks, so he was readily available to Blacks Agency. A senior member of the group was John Wesley Woodward (cello and string bass), who had been born in West Bromwich in 1879 but well trained musically later in Oxfordshire. He had played a great deal in string quartets and also had a lot of experience in ships. The final member, Georges Alexandre Krins (violin), had been born in Paris Li ge , Belgium London

The average age of the musicians was just 27.

How sad it all was. And spare a thought for poor Miss Steinhilber, silently weeping in Southport .

|

| Another photograph of Ted |

Our photo is of Mr. William T. Brailey, who was a member of the now famous and heroic orchestra of the Titanic. Mr. Brailey was at one time associated with Mr. Compton Paterson at the Freshfield aerodrome, and Mr. J. Gaunt at the Southport hangar. He was also a member of the Southport Pier Pavilion Band. He was engaged to a well-known Southport young lady.

==================

I knew virtually nothing about the musicians of the Titanic until I visited the Maritime Museum in Liverpool in 2011. The special display about the Titanic was so moving and absorbing that I wanted to know more about the 'local' musician. I headed the next day to Freshfield and Southport Pavilion to see where Ted had passed many hours.

==================

I knew virtually nothing about the musicians of the Titanic until I visited the Maritime Museum in Liverpool in 2011. The special display about the Titanic was so moving and absorbing that I wanted to know more about the 'local' musician. I headed the next day to Freshfield and Southport Pavilion to see where Ted had passed many hours.